Exhibitions

Exmouth Market

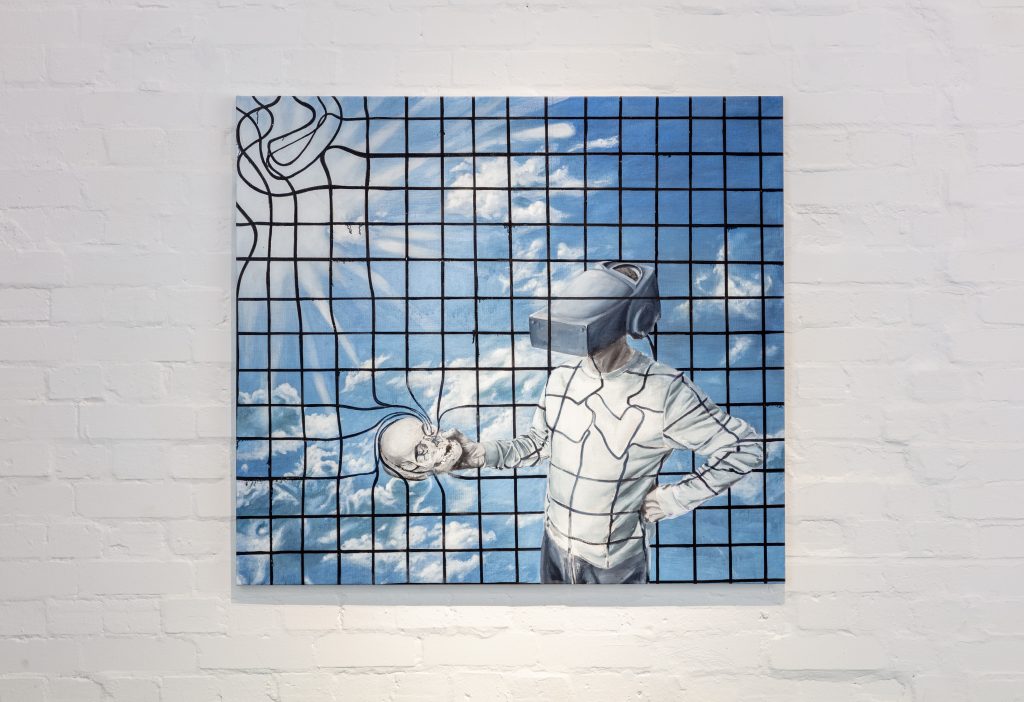

Elizabeth Xi Bauer is pleased to present 'We Lost Lots of Beautiful Things', a two-person exhibition bringing together works by Jandyra Waters (b. Brazil, 1921–2025), who was considered one of the pioneers of abstractionism in Brazil, and contemporary artist Theodore Ereira-Guyer (b. UK, 1990). Private View: 9th October 2025

Deptford

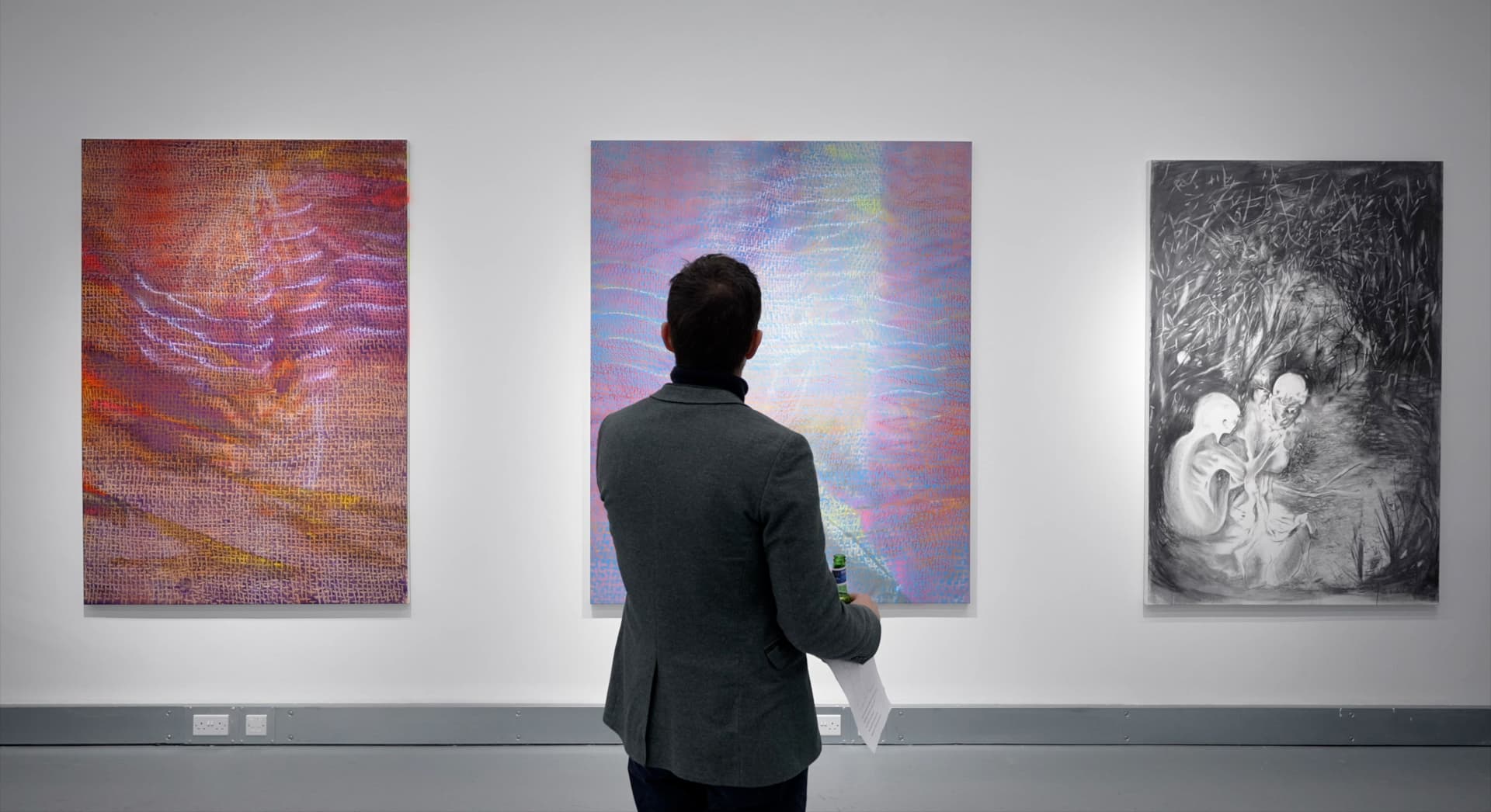

Elizabeth Xi Bauer is pleased to present 'The Fabric of Life', a duo exhibition by Petra Feriancová and Amanda Kyritsopoulou at EXB’s Deptford space. The exhibition is now extended until 15th November 2025.