Exhibitions

Deptford

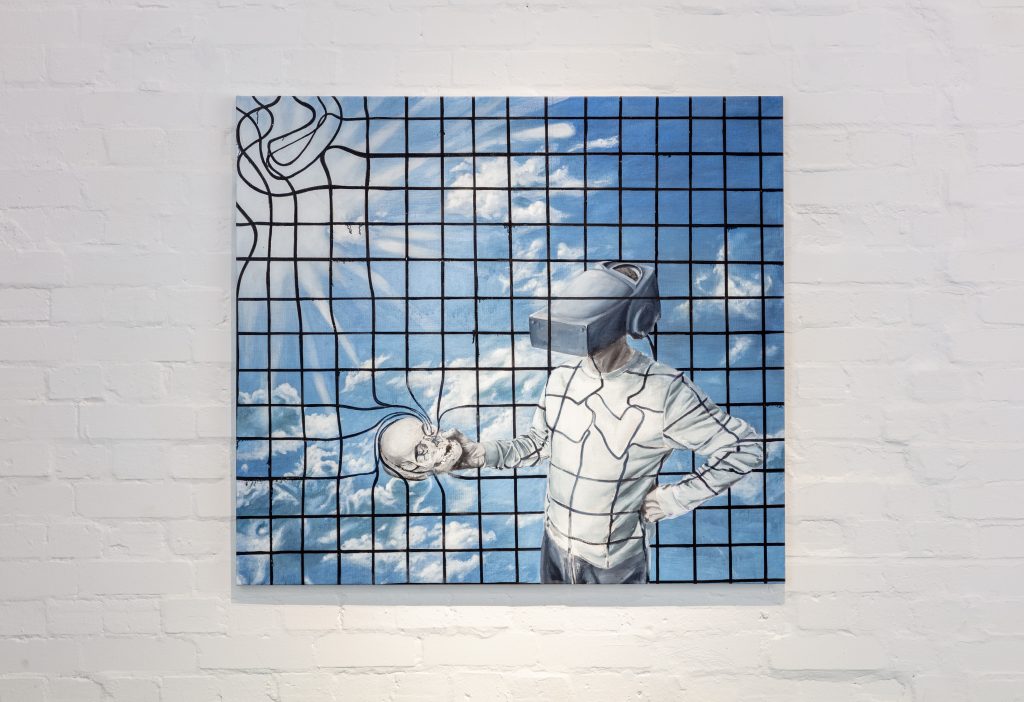

Thiago Barbalho: 'Chants' at Elizabeth Xi Bauer, Deptford 16th May – 28th June 2025 Private View: 15th May 2025 Elizabeth Xi Bauer is delighted to present 'Chants', a solo exhibition by artist Thiago Barbalho. Known for his intricate and evocative compositions, Barbalho’s latest body of work delves into the complexities of language, symbolism, and the intersection of identities.

Off-site

Liszt Institute London is proud to present 'Just Silence', a solo exhibition by ceramic artist Marta Jakobovits, in collaboration with Elizabeth Xi Bauer Gallery.

Exmouth Market

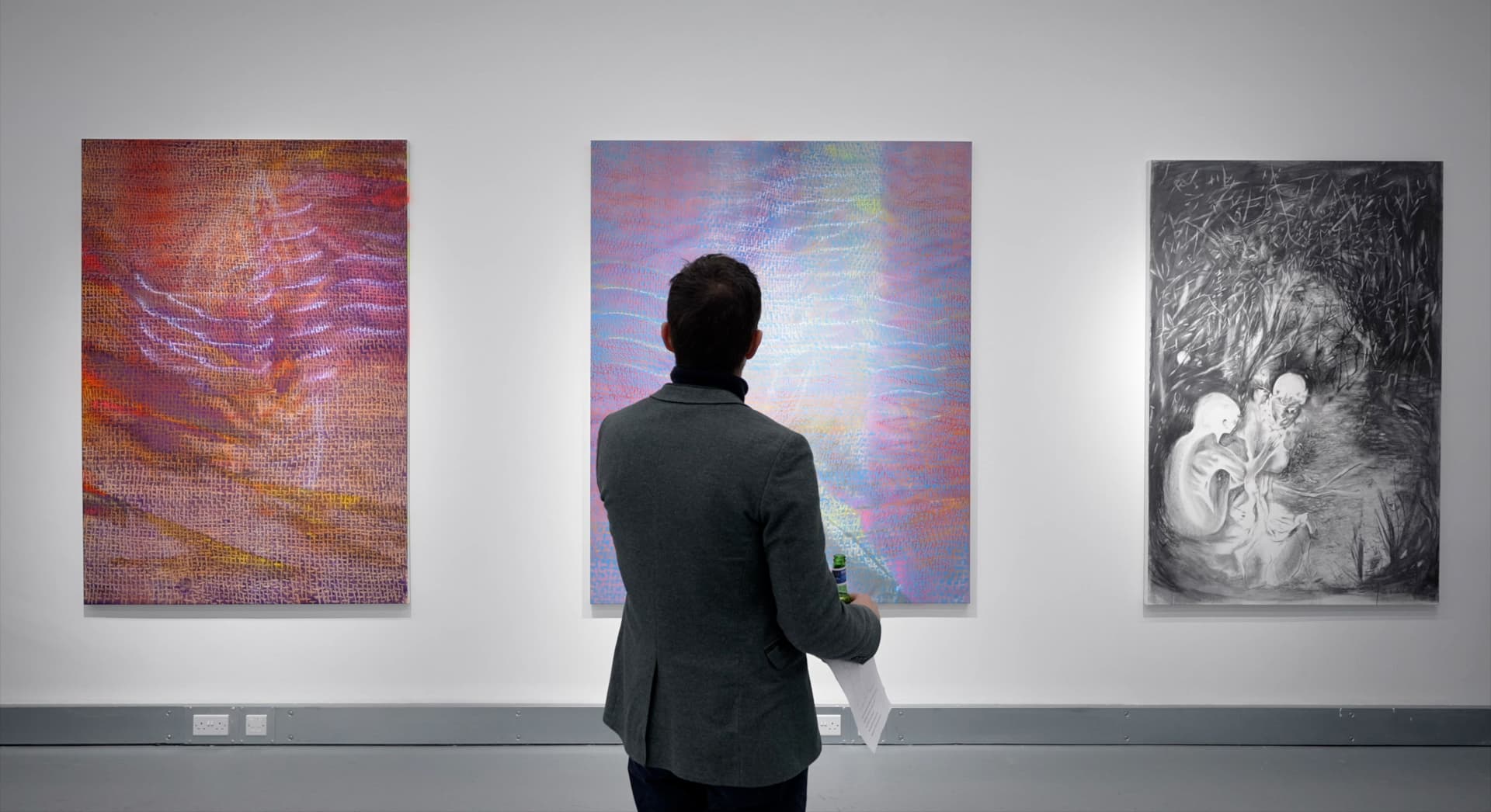

Elizabeth Xi Bauer presents '+ Days + Nights', an exhibition of works by contemporary artist Abraham Kritzman and Belgian abstractionist Philippe Van Snick, whose oeuvre combines the heritage of modern abstract art with the conceptual explorations of the 1970s. This is the first time these artists’ works have been in dialogue. Private View: 10th April 2025.