Exhibitions

Deptford

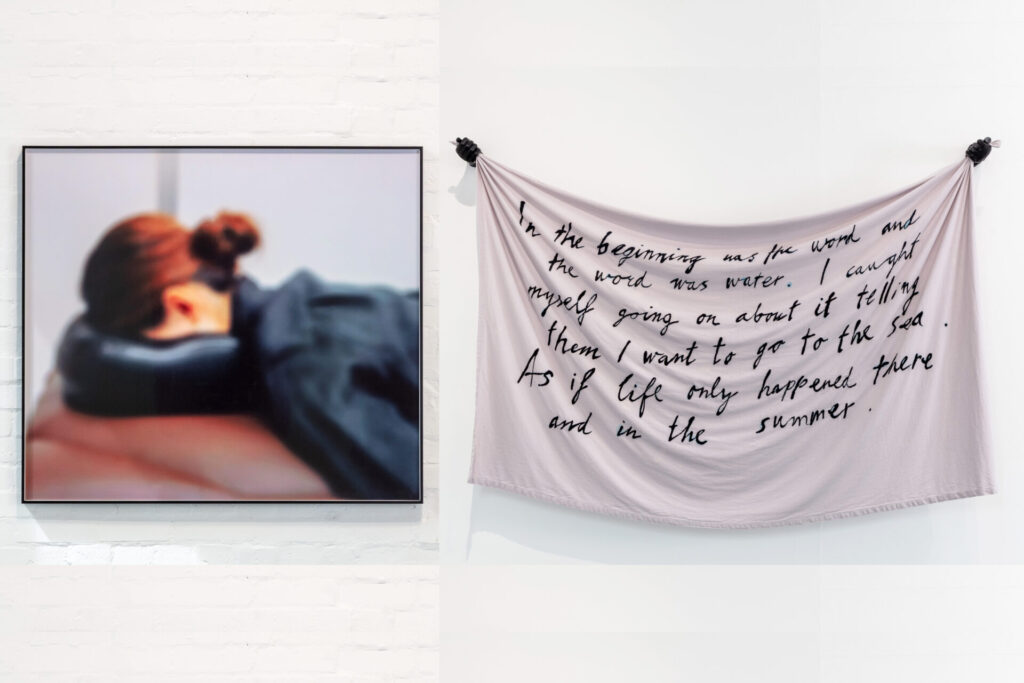

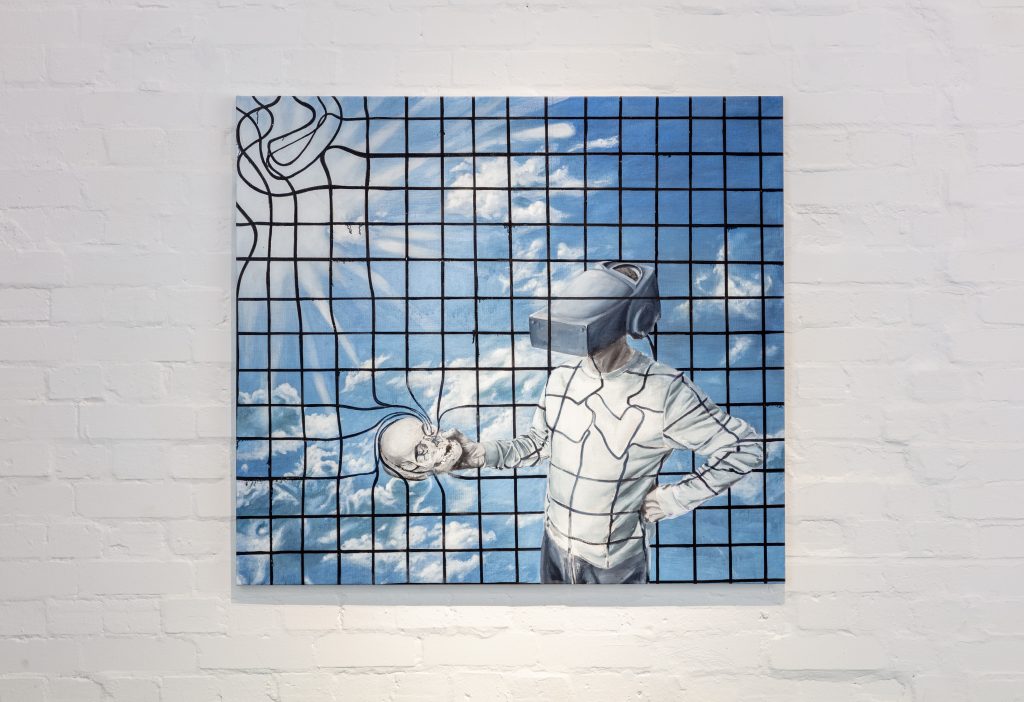

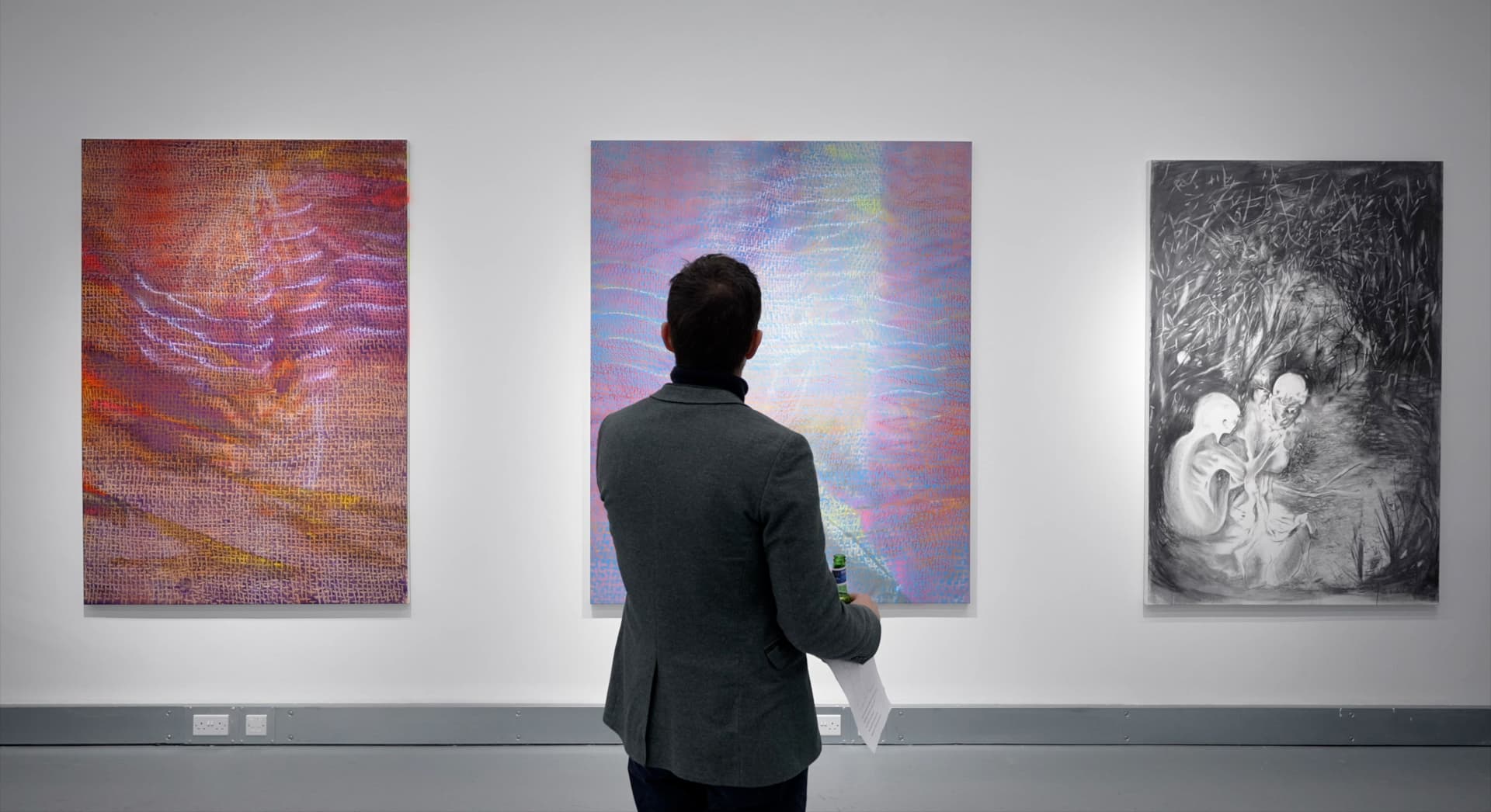

Elizabeth Xi Bauer is delighted to announce its annual summer show, a group presentation featuring four contemporary artists, Shadi Al-Atallah, Petra Feriancová, Amanda Kyritsopoulou, and Marie-Сlaire Messouma Manlanbien. Private View: 31st July 2025.