Exhibitions

Exmouth Market

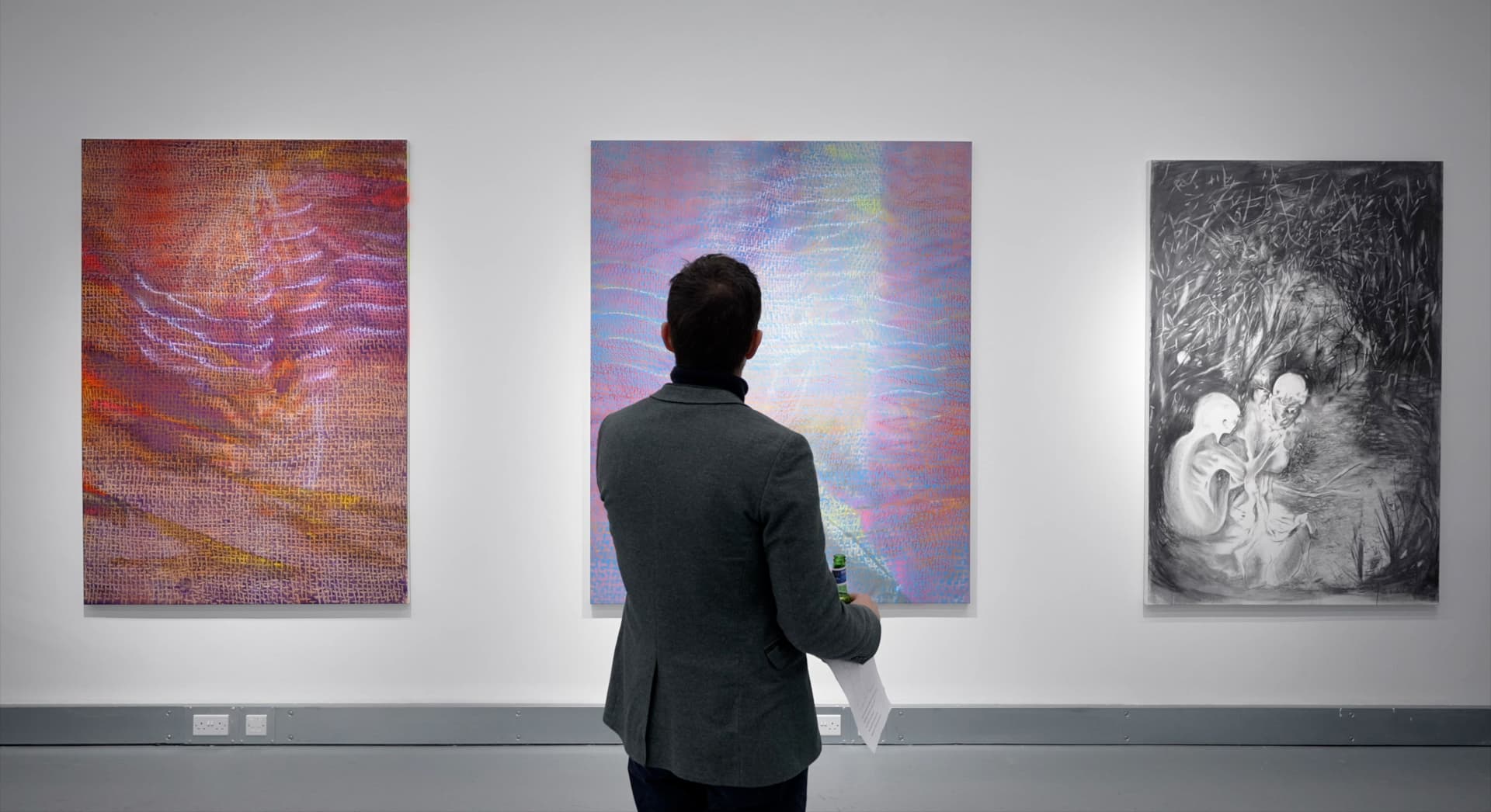

Oswaldo Maciá

Migratory Movements

5 Dec 2025 - 15 Feb 2026

Elizabeth Xi Bauer presents 'Migratory Movements', a solo exhibition of new works by acclaimed artist Oswaldo Maciá, developed during his 2025 residency at the gallery’s studio. Private View: 4th December 2025.

Deptford

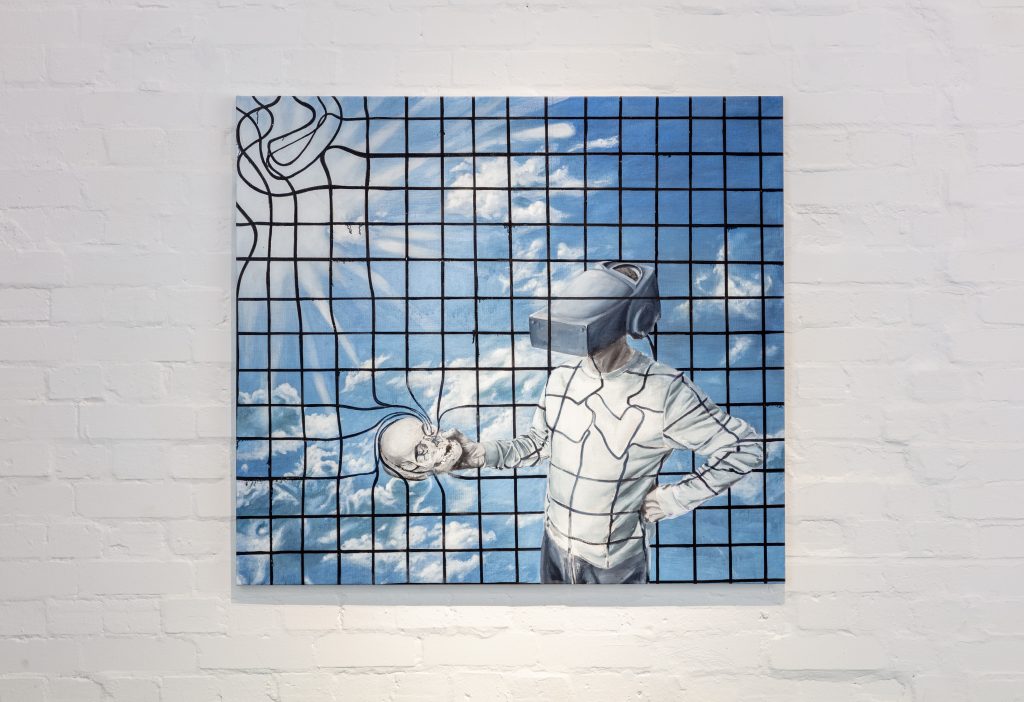

Shadi Al-Atallah

COBRA

28 Nov 2025 - 24 Jan 2026

Elizabeth Xi Bauer is pleased to present 'COBRA', an exhibition of new works by Shadi Al-Atallah, at EXB Deptford.