It is hazy here, by the pool or in the forest. Yes, there are still lions or people like lions1. But all the animals are tired out, or still learning their lines, and I’ve forgotten – again – where we are. The shoot is over, or has not yet begun, and the faces around me are from some past you thought I knew.

But everything has become so difficult to decipher: have we been here before? Bronze suns hang squishy above a toothpaste tortoise. Corbels crumble, glint blankly beneath aluminium moons. Somewhere, a tree writhes up the margin of a text. Each looped descender a tendril wrapping tight around the promise of a future2. When every dream is a gemstone, who would wish to wake from this gilded sleep?

On remembering

When the philosophers arrived, they told us a story3. They sought to make things clear, to show once and for all the difference between memory and imagination: the one to be excavated from the earth; the other built up to the skies. Picture, they said, a painter. One day she paints a beautiful landscape – an earthy metal place of gemstone shores and pale-trunked trees – and everybody wondered where this place could be. I dreamed it, said the painter, and we believed her.

But no, said the philosophers, who claimed to know the art better than the artist. The painting, they said, shows a place that the painter had visited long ago, once upon a time, in her childhood. You must have forgotten it, they told her. Or forgotten that you had remembered it. Or imagined that you dreamed it. Or simply lied. The philosophers ask us not to trust the artist who they themselves have conjured in this illustrative fiction. They ask us to trust instead a theory – one at risk of dissolving before this ink is even dry. But why?

On etching

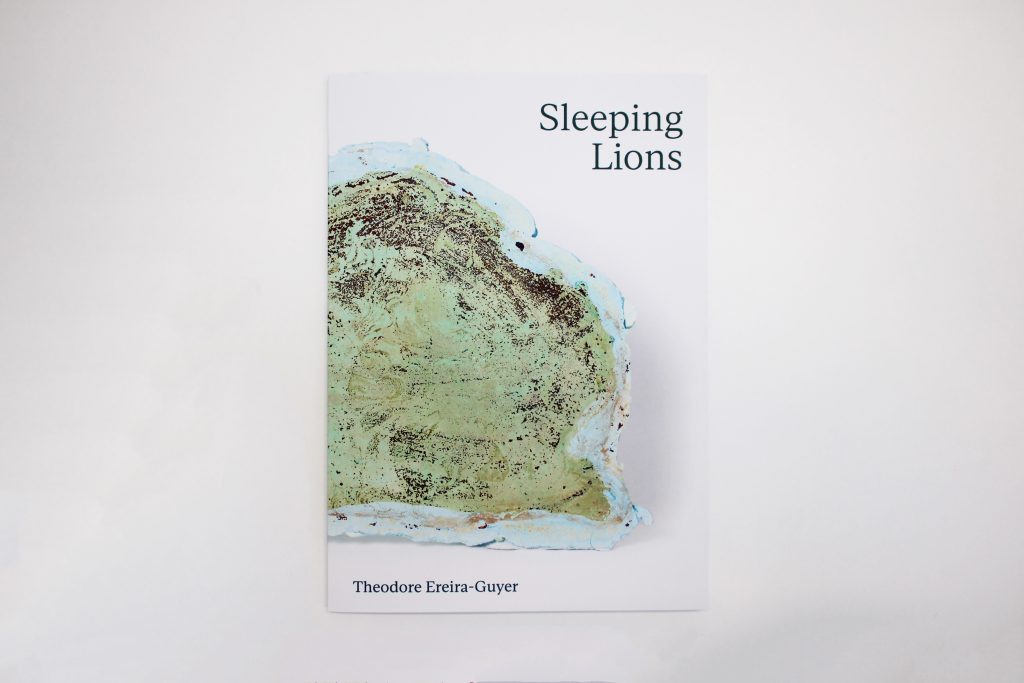

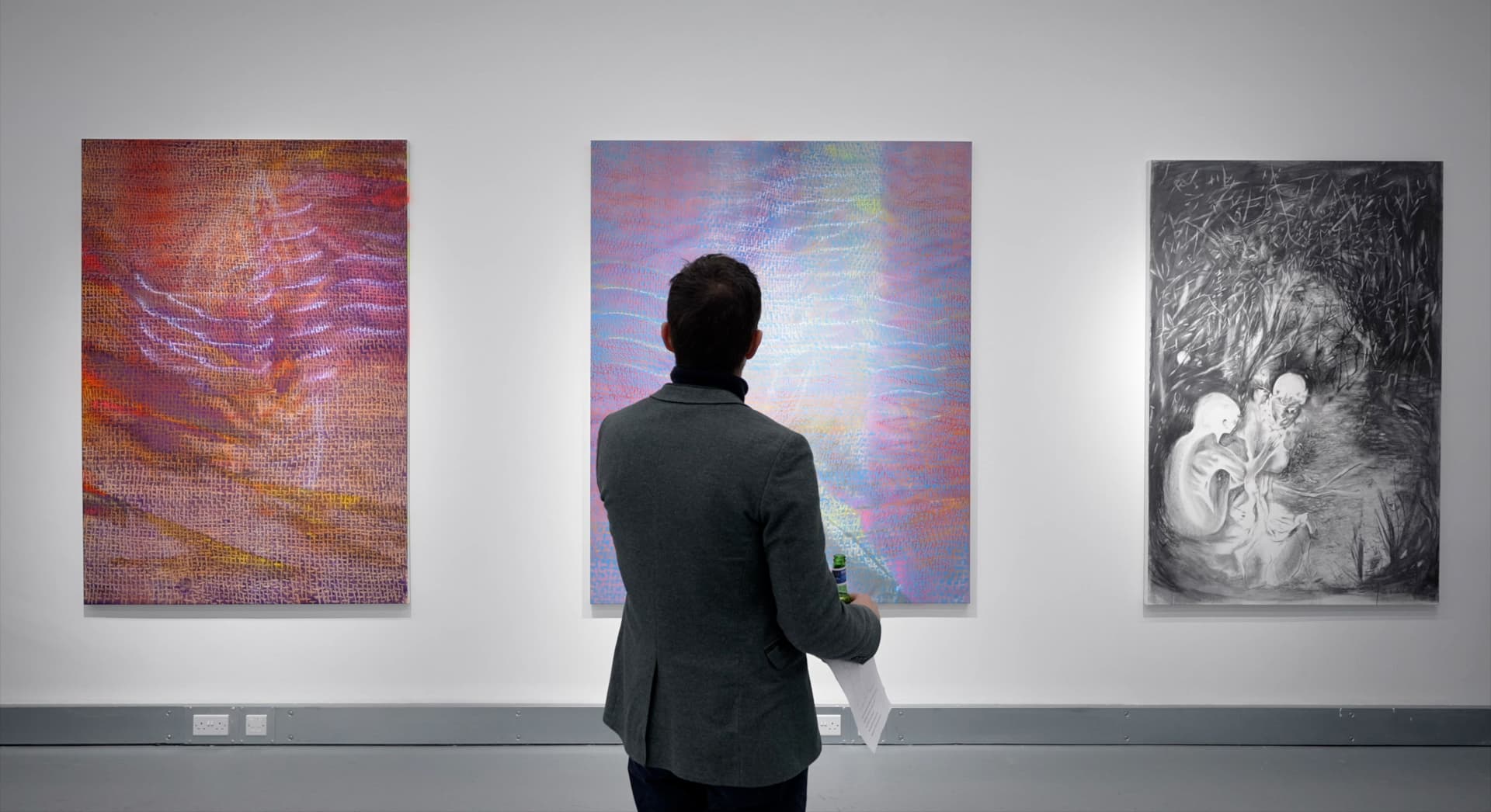

The printmaker’s studio is like somewhere between a home and a factory. Industrial processes take place at domestic scale. Before his latest exhibition with Elizabeth Xi Bauer, Theodore Ereira-Guyer moved into a new studio in south-east London. From there, he has been developing a way of working that he first began to test in Brazil in 2020. It’s a technique that creates tones of earthy shimmer and speckled, roughly dappled textures that feel like they’re on the verge of disintegrating.

In London, Ereira-Guyer has been able to hone the technique and increase the scale at which it can operate. The process itself is complex. It begins with a sheet of steel, which Ereira-Guyer paints over with different varnishes using stiff old, hardened brushes. He doesn’t really sketch, instead merging multiple source materials as he works to form archetypal or dream-like non-places – deeply resonant but impossible to place. A garden scene, for example, might layer together a botanic garden in Brazil with a public park or the garden of a beloved relative. A desert might in fact be based upon sand dunes in Portugal.

These emerging images – real, imagined, and remembered – are then washed over with a mop dunked in a bucket of acid, left to rust, wiped down, painted over with inks, wiped again with scrim. Things blur, dissolve and reveal themselves again. Dry pigments like glass powder might be added too. Some plates are kept quite simple, with no ink, only varnish and the fast-developing rust. Other works bear testament to Ereira-Guyer’s material exuberance, punctured or encrusted with oak galls, gum arabic, safflower, or annatto seed. I’m intrigued about the use of these organic materials within a process replete with toxicity. Containers around the studio are labelled with things like ferrochloride or copper sulphite. Etching is a process of controlled corrosion.

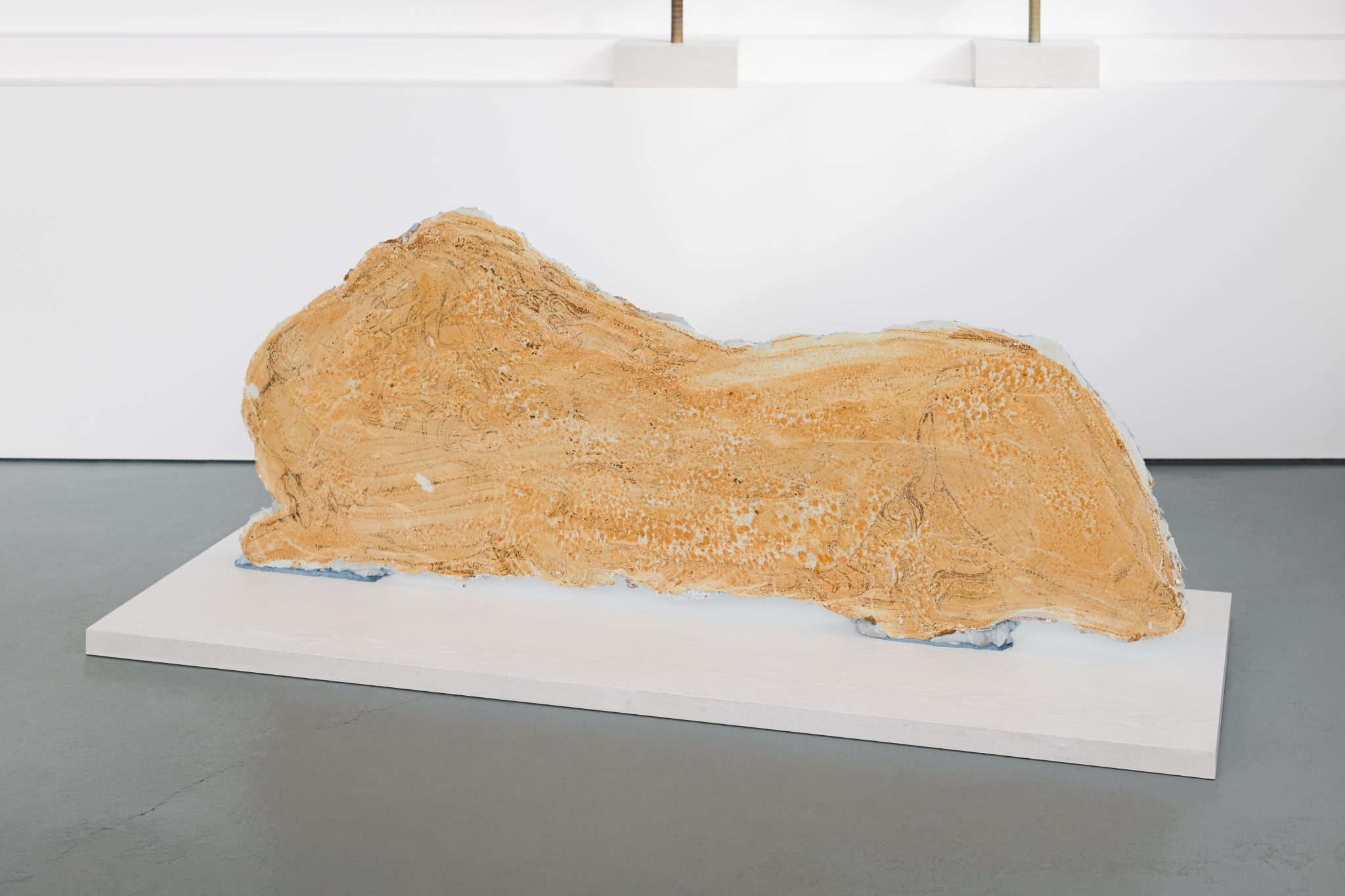

At a certain point, the plate is then pressed into a specially prepared ground: plaster piped over a fibreglass quadraxial mesh, which is held together by an aluminium frame. The obverse of these works shows this aspect of their construction through blobby trails of pink or jade-hued plaster. Plate and ground are then left overnight to rest and bleed together before being separated from one another in a dramatic reveal. In embedding pigment into plaster, the technique has something of the fresco. Memory, therefore, becomes architecture, even as Ereira-Guyer continues to draw across the surface with charcoal. A palace, after all, is a storehouse of dreams. And there is no archive without a place to put it.

The lion

If a lion is breathing the same air as a tortoise, we know you must be in the realm of the fable. And you know therefore that each animal is not simply here as itself, but as a representative – maybe even an ambassador. The lion, of course, is the very model of sovereign strength: roaring, regal, running rampant through the history of heraldry. The courtier counsels the prince that to frighten the wolves he must act like a lion (and sometimes like a fox to deceive his enemies)4. But here, these lions lie still, luxuriantly idle, asleep as they are in life or carved in marble before the tombs of popes5.

In a magical forest, a group of peasants prepare to perform before royalty6. The forest may seem beyond the realms of certain societal norms, but the stratifications of class run deep, and this cannot be forgotten, no matter how lush the undergrowth. Having decided who shall play the lion, the peasants then worry that the aristocracy will be unable to distinguish between the play and reality. While their anxieties are gendered (it is only “the ladies” they are concerned for) perhaps they are right to suspect that societal elites are often insulated from the need to confront certain truths that others may not be privileged enough to ignore. There is a lot going on here. But what I’m interested in is the figure of an actor, playing a peasant, playing a lion. The archetypal play within a play. In failing to appreciate how their dramatic talents render their repeated insistence that “this be a play”, the peasants are portrayed as entertainingly absurd. But they are at least considerate of their audience. The watching aristocrats are altogether charmless in their self-consciously elevated repartee.

The tortoise

The tortoise, of course, is always slow – protected, persistent, inevitably triumphant in the fables of the ancients. The lion and the tortoise. Only in myth or art – or the collecting mania of the colonial imaginary – could the two ever meet. And what happens now when they do?

In a country house on the outskirts of Paris, a wealthy white man devotes himself to a life of sensuality7. Dissatisfied with the hues of a Persian carpet, he buys himself a tortoise, believing that its dark shell, slowly moving around the room, will perfectly offset the colours of the carpet. But he is disappointed and chooses instead to have the tortoise’s shell encrusted with an array of rare gems – opals, peridot, almandine, and aquamarine – until the tortoise’s glimmering shell reminds our decadent subject of “the scales of tartar that glitter on the insides of wine-casks”. While gazing at the tortoise, the narrator pours himself a glass of whisky, the “acrid carbolic bouquet” of which gives rise to the memory of an urgent and bloody visit to an unskilled backstreet dentist. Time and space collapse upon each other via the vividness of a memory borne in a scent, until the moment when the vision dissipates, and the man realises that the tortoise – accustomed, we’re told, to a modest existence and “unable to bear the dazzling luxury imposed upon it” – has ceased moving. It soon becomes obvious that the tortoise is dead.

How to deify your lover

When news came to the emperor that his beautiful young lover had drowned, he was heartbroken. His mind paced back and forth. Back to their sweetest memories – slaying that lion together in north Africa, commissioning the poets to sing of their heroics, the swiftness of their steeds, the sharp brass of their spears8. But his mind roamed forward too – to the abyss that opened before him upon the boy’s sudden death. Unable to cope with the reality of loss, the emperor responded in the only way he knew: by perpetuating a fiction. So, he had his lover transformed into a god. Deification, as you know, is a process of image production – an almost feverish urge to represent the beloved repeatedly over and over again. Friezes, statues, coins, medallions: the emperor dictated that all would bear the image of his lover: the tall, athletic physique, the curling locks, the downcast face.

These images spread. And so too did the name of the lover, to be worshipped far and wide. But only for a time. One feverish belief replaced another, and the downcast faces of the lover were obliterated by paroxysms of iconoclasm. In time, those visages that did survive faded in the sun, cracked and crumbled under acid rains. They still face us, but can we remember who they are? Truths, it was said, centuries later, are illusions that have forgotten they are illusions, coins which have lost their embossing, and are now simply metal9. In the end, the philosophers made their decision: we remember together, they said, but we dream alone. The emperors, it seems, are proliferating again, while eternal youth lives only in stories now.

1. Werner Herzog in Burden of Dreams (1982)

2. William Blake, ‘The Little Girl Found’, in Songs of Experience (1794)

3. CB Martin and Max Deutscher, ‘Remembering’, in The Philosophical Review Vol. 75, No. 2 (April 1966)

4. Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince (1532). See Jacques Derrida, The Beast and the Sovereign Vol. 1 (2009)

5. Antonio Canova, Monument to Clement XIII (1758-1769)

6. William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1605)

7. Joris-Karl Huysmans, À rebours (1884)

8. Pancrates, ‘The Lion Hunt’ (2nd century BCE)

9. Friedrich Nietzsche, On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense (1873)