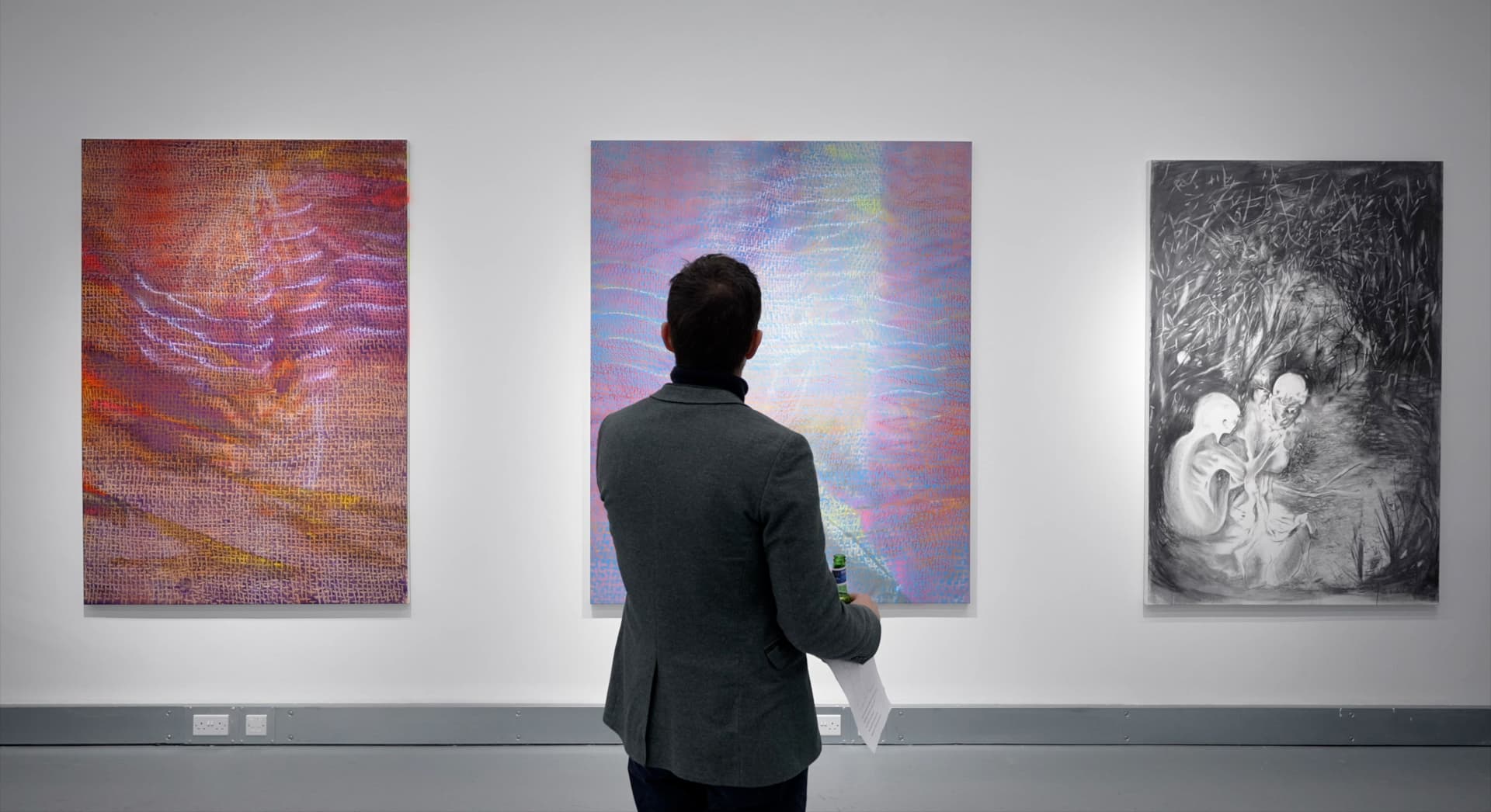

The Immortal

15 Jul - 14 Sep 2022

Deptford

Featuring Caroline Achaintre, Lorena Ancona, Tonico Lemos Auad, Dan Coopey, Marta Jakobovits, and Antonio Pichillá Quiacaín.

Curated by Maria do Carmo M. P. de Pontes

“We accept reality so readily — perhaps because we sense that nothing is real.

I asked Argos how much of the Odyssey he knew.

He found using Greek difficult; I had to repeat the question.

‘Very little’, he replied. ‘Less than the meagerest rhapsode.

It has been eleven hundred years since last I wrote it’”.

A dialogue from Jorge Luis Borges’ short story ‘The Immortal’,

between the narrator Marcus Flaminius Rufus and Homer.

Imagine that, after escalating tensions, your country is suddenly at war with a neighbouring country. Your city is of strategic importance and easily accessible by land, sea and air; without forewarning, you must draw up an evacuation plan and leave your home in a rush. What would you take with you? What are the precious things, material and immaterial, written or spoken, that you would choose to carry within and pass on?

Or try picturing a scenario where, an illness that at first seemed like an epidemic, not unlike others seen before, is suddenly discovered to be incredibly contagious, leading to a global pandemic in a matter of weeks. Unable to travel, socialise, go to work or even run small errands outdoors – in fact, you are unable to leave your place at all – you are faced with a reality where, perhaps unlike ever before in your life, you must rely on your own skills for nourishment, entertainment and indeed, survival. Which abilities have you gathered so far that could be instrumentalised to make life – yours as well as that of others – more meaningful?

Such tragedies have inspired The Immortal, an exhibition that brings together six artists whose work could be regarded as answers to the above questions. Their production is concerned with the research and practice of vernacular knowledge, as well as with perfecting craft techniques that have been around since time immemorial. Working across ceramics, basketry, weaving and embroidering, each of them come from, live and work in various parts of the world.

Caroline Achaintre’s textiles and ceramics are essentially abstract, yet they nod towards the animated world – whether by resembling masks that one could wear, or bugs that mimic their environment, and at times both animal and human at once. Born in France, raised in Germany and now having lived in England for decades, her practice equally amalgamates various influences, such as Primitivism, German Expressionism and Post-war British sculpture. Alberich (2022) is a hand-tufted tapestry that at first seems like an oversized jacket – though ironically, in German mythology, Alberich is a dwarf, who was defeated by Siegfried and his invisibility cloak. The tapestry could also be read as the head of a fantastic furry animal, with big luminescent eyes. This Rorschach-like quality is formative of Achaintre’s practice and is further reinforced by the fact that most of her works are symmetric. Akin and Sir Plus (both 2019), two ceramic wall works that resemble masks, follow the same logic.

Lorena Ancona’s approach to ceramics takes the viewer to Pre-Colombian times, both in the way that the objects are manufactured and in terms of what they represent. Rather than moved by nostalgia, the artist is curious as to how these ancient skills and cosmogonies can serve to understand the present and, while doing so, further help us deconstruct Eurocentric historical narratives. Ancona nurtures a deep respect for nature, which abounds in her work through the representation of thunders, fire, shells, precious gems and so on. Kawil as thunder (2022) consists of a rope fixed to the ceiling, with ceramic elements attached to it. Each of the ceramics represent things such as flowers, water and bones, which in turn allude to other symbolisms. The work is tinted using an ancient Mayan technique called limewash – achieved by crushing and burning limestone – which gives way to subtle pastel tones.

Notions of tradition and cultural heritage are at the heart of Tonico Lemos Auad’s practice. Found objects are often the starting point of his artworks, yet not the mass-produced ones: Lemos Auad selects articles that were originally handmade – or suffered alterations through the passage of time, thus displaying clear signs of usage – and intervenes through a conceptual approach. This labour of love results in textile and wood works that are unique in the purest sense of the word. Buffalo (2020) is a sculpture in two parts made of reclaimed Iroko wood, to which the artist has attached linen fragments that appear to emerge from the wood’s imperfections, filling them both materially and poetically. Untitled/ Column (2022) is a single demolition wood block with spikes carved on top; here the ropes don’t emerge from the work but rather embrace it, through a delicate choreography of shibari knots. The artist also exhibits a series of embroideries called Índio (‘Indigenous’, in a direct translation), that are inspired by the elaborate face paintings of indigenous communities – particularly that of the Carajás tribe, from central Brazil. Each of the face paintings serve a different ritualistic purpose, a richness of colours and shapes that is emulated by the artist in his compositions.

Sculptor Dan Coopey works predominantly with basketry – a form of art so old that in all likeliness it predates ceramics. Using different natural fibres, the artist weaves shapes that go way beyond vessels, and with no plan drawn before making, embraces chance. Stack (2021) is a somewhat clumsy raffia structure that resembles a creased wizard hat with a pompom atop, displayed over a wooden crate. As with many of his works, there’s a chewed gum hidden somewhere in the work – that is, an element with the artist’s genetic material, which can be seen both as the ultimate way of claiming authorship over, or a clue for future archeologists to date the object. In essence, the gesture points towards a concern with the passing of time that runs through Coopey’s practice: the time consumed while he painstakingly weaves the works, the agency of time-passing in the colouring of the sculptures, and so on. In recent years he started using eggs on his works, an object that, as of the fibres, possesses myriad variations of colour, texture and form – within a strict margin of its objecthood.

Romanian grande dame Marta Jakobovits has been restless in exploring the possibilities of ceramics for over five decades. Her approach to sculpture making is analogue to that of an alchemist, in their shared pursuit of sourcing raw materials and observing how they react to different environmental conditions such as heat, humidity and so on. Noteworthy, in the captions of the works she states the temperature in which the ceramics were burned, in addition to the materials that were employed, reflecting the unique experience of each heating process. Though she favours abstract shapes in her compositions – both geometric and organic ones, the latter alluding to the unprocessed matter as it exists in nature – she has cast the human body at times. Anticipation, Presentiment and Something is about to happen (all 2022) are three ceramic pieces in the form of a square. They are all grey in tone and abstract, though each possess unique patterns and motifs.

Antonio Pichillá employs the techniques of a weaver who, with threads and yarns, devises elaborate compositions. Many of them are made using the four colours yellow, red, black and white, which are associated with corn in his native Guatemala. Corn plays a central role in this region, economically and culturally, its presence found in nearly every meal. Even more so, corn serves as basis for the foundational myth in Mayan culture, which establishes that the first humans were made out of corn; the four colours corresponding to body parts. Camino (something like ‘Path’) (2019) is a work in which handwoven cotton stripes are interwoven, thus forming a beautiful abstract geometric composition. On show is a yellow version, but a red one also exists. Semilla (Seed) (2020) is another wall work made of dozens of wool yarns pending from a wood board. Rather than woven, here the yarns are loose, moving with the smallest of winds. In Abuelo (Grandfather) (2021) Pichillá deconstructs a pair of trousers that are usually used by men within his Mayan Tz!utujil heritage, placing the colourful belt as a snake atop of the composition. Noteworthy, weaving is an activity traditionally associated with women, thus the title also plays with gender roles.

The Immortal is the opening tale in Jorge Luis Borges ‘The Aleph’, first published in Spanish in 1949. With twists and turns that are characteristic of the Argentinian author’s style, it tells the story of a man who unwillingly achieved immortality, and his subsequent quest over the centuries to lose it. Whereas immortality of the flesh must be a burden – and a frivolous pursuit – this exhibition is a praise to the immortality of that which matters.

Related Content